Book Review: A Land We Can Share

I’m a graduate student in inclusive education, and I love books and reading. When my kids were born one of the first things I dreamed about was reading with them.

So I was very excited to come across this book by Paula Kluth and Kelly Chandler-Olcott. It’s about helping kids on the autism spectrum grow in literacy. And it’s definitely in my top three favorite books about autism. Here’s why.

1. This book goes to the source.

The starting point for the authors of this book was the experience of literacy learners with autism. To prepare for writing, the authors reviewed 16 book-length autobiographies to ask,

- What do people with autism spectrum labels who write autobiographies report about their development of literacy?

- In the view of people with autism spectrum labels, what aspects of their homes and school communities supported them in developing literacy?

- What instructional practices for supporting students’ literacy development might be suggested by the accounts of these individuals? (p. xxiii)

As a result, the book is a unique combination of reflections by people with autism, and strategies based in educational best practices to support learning in inclusive classrooms.

2. Defining literacy helps us set a direction.

Before we can teach literacy, we have to know what it is. Chapter 2 lays out some foundational ideas.

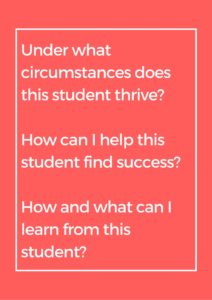

First, the concept of presuming competence. This, at the simplest level, means that we see a person who is labeled autistic as a thinking, feeling person. This means that when a student does not show us what they know or can do, the teacher’s job is to think about what other approaches could be tried, to support connection, communication and learning (p. 33). We assume that a person always has the potential to learn and to grow.

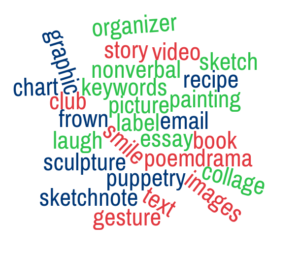

Second, the idea of multiple literacies asks us to value a wide range of literacy skills, which students may not be able to show us in ways that are easy to measure. “Students demonstrate literacy when they act out a scene from a favorite movie, page through a book, have a conversation, listen to the teacher read a poem, illustrate an idea, tell a joke, or show a peer how to use their communication board or sign system.” If a child is receiving or sharing information or ideas, they are practicing literacy.

Second, the idea of multiple literacies asks us to value a wide range of literacy skills, which students may not be able to show us in ways that are easy to measure. “Students demonstrate literacy when they act out a scene from a favorite movie, page through a book, have a conversation, listen to the teacher read a poem, illustrate an idea, tell a joke, or show a peer how to use their communication board or sign system.” If a child is receiving or sharing information or ideas, they are practicing literacy.

All literacies are valuable, all literacies happen within a social context (because literacy is about communication), and all literacies serve a social purpose. Literacy, then, is also about relationships.

3. Autism is described as a list of differences, rather than a list of problems.

Autism is viewed here through the social model of disability: “…we recognize that some people have severe struggles, challenges and impairments due to their disability, but we also understand that those same individuals may be more or less disabled by the barriers that exist in a society that does not take account of their needs and differences…some individuals with autism indicate that the most disabling aspects of their lives are the attitudes, perspectives, and actions of those without labels (p. 4).”

In this chapter, autism is described in terms of movement differences, sensory differences, communication differences, social differences, and learning differences. For each, implications for literacy are also explored.

I have often used this list of characteristics of autism to frame discussions with my children’s classmates, and to help them understand that we are not so different.

4. Literacy is inclusive.

Because literacy is a social activity for social purposes, it only makes sense to think about it in terms of inclusive classrooms. Children with autism benefit from the same kinds of good teaching that any child would. In addition, children with autism benefit from the modeling provided by typical learners and communicators.

Chapter 3 explores seven principles for promoting inclusive literacy:

Chapter 3 explores seven principles for promoting inclusive literacy:

- maintain high expectations

- provide models of literate behavior

- elicit students’ perspectives

- promote diversity as a positive resource

- adopt “elastic” instructional approaches

- use flexible grouping strategies

- differentiate instruction

As well, chapter 7 has a specific focus on literacy learning for students with more significant barriers to communication. Literacy is for everyone, and the authors of this book make that very clear.

3. There is a chapter on assessment.

Assessing the knowledge and skills of students with autism can be really difficult to do with accuracy. We have to be very careful to remember that we can know a part of a student’s capabilities, but that by no means will tell us all they know and can do.

Part of the problem is the nature of formal assessment. Tests are designed to be given to children who know how to write them, and who are either compliant or willing to do their best. Neither may be the case for a child or teen with autism, but that doesn’t mean they are not capable or knowledgeable.

It’s important, then, to be able to assess in authentic ways – observing what a student does and shares in his or her daily activities. Some useful suggestions are made here, both about accommodations and interpretation of the results when formal testing is necessary, and about “out of the box” ways to assess learning.

6. This book is very, very practical – with many ideas for teaching and learning.

Chapters 5 and 6 focus on reading, writing, and representation. Each chapter breaks down learning into important components: phonics, fluency, comprehension, vocabulary, writing fluency, planning and organizing, revising and editing. Each section has considerations about kids with autism to keep in mind, and many suggestions for instruction.

7. The best part: what’s good for kids with autism is good for everybody.

The day is long gone – if it was ever true – when we could just present kids with information and instructions, and expect them to absorb it. Every person has strengths and challenges in learning. Everyone benefits from approaching learning in multiple ways, and from having the freedom to express what they’ve learned in ways that fit their strengths.

The perspectives and teaching ideas in this book are good for all learners, because by approaching students as individuals, we give everyone an opportunity to thrive. This book is really about good teaching.

So there you have it – six reasons why this is my favorite book about literacy.

If you are a teacher, you should buy this book. If you aren’t, you might want to buy it for your child’s teacher.

“Given that we seek the small and manageable, it is no surprise that high-functioning autistic people, unable to communicate with others above the ringing swirl, shout across the canyons of reality by writing…There we find a peaceful world of art and order, a land we can share. Thus, writing was my salvation. I have said in the past, and I have since heard it repeated by other autistic people, that written English is my first language and spoken English is my second. Since I was five years old, I have written all the wonderful and terrible things that I could not bear to share.”

Songs of the Gorilla: My Journey Through Autism by Dawn Prince-Hughes, p. 25-26 (2004).

Further Reading:

Paula Kluth has written many books on the topics of inclusive education and autism. She is also active on Facebook and Twitter, and you can find links to those books and other resources on her website: www.paulakluth.com

Hi Deborah ,

Thank your. I love your review but i didnt know from where to buy the book . Luckely i found it on http://justreadbook.com (I don’t know if i can leave a link ) but i think it will help others too. I like the book ” A Land We Can Share” and also i recommend others to read it.

Thanks, Vincent.

Glad you liked it! Thanks for letting us know. The book is also available on Amazon.