Sketchnoting: Supporting Communication for Visual Thinkers

In September 2017, CTV Montreal reported on Ellis, a minimally-verbal boy with autism. The story was that one day, his parents discovered that Ellis “could think, could talk, through pictures.” His father had begun drawing household items and simple situations in an effort to connect, and Ellis drew back in response. Over time, Ellis also began to make changes to his father’s drawings to assert his own perspective. Over time, the drawings expanded to include family, friends, and community. “One drawing depicts his classmates cheering him on because he stopped crying at school – a sketch that marked the end of Ellis’ behavioral issues,” and a tipping point in his self-awareness.

In her book Dancing with Max, Emily Colson tells a similar story about her son, who was able to communicate with his mother by giving her direction as she drew for him. It became an important way for him to express his needs and hopes, and also his memories.

Drawing to Support Communication

One of the most important things we can do for our children is to help them find ways to be understood. Communication is power – it allows us to express our thoughts, build relationships, set boundaries, advocate for what we need, and contribute in our communities. Often, people with autism have difficulty with oral communication, so it’s important to look for alternate ways to express ideas that might better suit the way a child thinks. We know that many (but not all) people of autism are visual thinkers – Temple Grandin described it as “thinking in pictures” in her book of the same name.

We also know that augmenting communication through strategies like sign language and AAC can actually support the development of oral language. What about sketching, then?

I’ve been intrigued by the idea of supporting communication through images for several years now. I found Emily Colson’s description fascinating, but the tipping point for me was in learning about PATH and MAPS person-centred planning. There I learned that creating images on paper as people tell their stories is an effective way to help a person or a group recognize values, experiences, and goals that are most important to them, and are a powerful memory trigger for future discussions.

Later on, I came across the strategy of sketchnoting. People like Sylvia Duckworth, Karen Bosch, Mike Rohde, Sunni Brown and others have created resources to explain why drawing and doodling is valuable as a communication and thinking tool, and to help people get started. One important myth to debunk is the idea that drawing is only for people who are good at it. Sketchnoting is about expressing an idea through an image – NOT about creating a work of art – although you may be pleased with what you can do when you try it out.

Getting Started

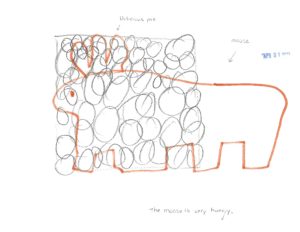

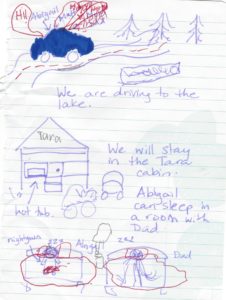

For years now, I’ve been encouraging my daughter to draw with me. Some purposes and strategies we’ve used:

use drawing as a way to support fun engagement and interaction. We’d put a giant piece of paper on the floor, and start to draw the things we talked about. We were fortunate to have family friends and respite workers who liked to doodle too. Harold and the Purple Crayon was a good book to read as a starting point.

use drawing as a way to support fun engagement and interaction. We’d put a giant piece of paper on the floor, and start to draw the things we talked about. We were fortunate to have family friends and respite workers who liked to doodle too. Harold and the Purple Crayon was a good book to read as a starting point.- draw to explain feelings or ideas. If I wanted to show her what was

going to happen, I drew doodles (sometimes with a checklist). I encouraged her to give me a few words to share her feelings or concerns, and drew what I heard. Sometimes I found this helped her tell me more. Sometimes she writes about how she is feeling, and why.

going to happen, I drew doodles (sometimes with a checklist). I encouraged her to give me a few words to share her feelings or concerns, and drew what I heard. Sometimes I found this helped her tell me more. Sometimes she writes about how she is feeling, and why. - draw to learn together. Last month we brought our sketchbooks to the Manitoba Museum, and I drew what I thought was interesting. She drew some of her own drawings in her sketchbook, and also helped me with mine. It’s amazing what you see when you slow down and look. We’ve also been drawing key images during sermons on Sunday, to help both of us focus and think about the meaning of what we hear.

Once you move into the realm of sketchnoting strategies, there are all kinds of ways you can use images to process and share information. You can sketchnote stories or videos or quotations. You can create sketchnotes to share key ideas for a school assignment or a message to a friend. Sketchnotes can be used in a group to brainstorm ideas and make plans. Sometimes we have an idea or a feeling that can best be represented by a symbol or an image. It’s really a form of literacy, with unique formats and ways of organizing information.

Learning More

There isn’t a lot about sketchnoting with kids who have autism, but Carol Gray’s suggestions in Comic Strip Conversations may be helpful, as well as the anecdotes of families who have tried it, like those at the beginning of this article.

There are now many resources meant for teaching all kids (and adults) the basics of getting ideas on paper in visual form. Some to check out:

- We Are Teachers: 8 Ways to Get Started With Doodling in the Classroom

- Creative Educator: Get Started with Sketchnoting

- The Cool Cat Teacher: Epic Sketchnoting Resources

- The Spicy Learning Blog: How I Teach Sketchnoting

- Karen Bosch’s sketchnoting resources for teachers. On this page, you’ll find a link to her iTunes U course that’s free and easy to explore at your own pace, as well as lots of examples from her classroom.

- Sylvia Duckworth’s Sketchnoting for Beginners presentation

- Mike Rohde’s Sketchnote Handbook

Drawing pictures isn’t a magic tool for communication. It’s simply one alternative way to connect and share ideas with your child. Not every child will be interested in sketching. For those who do like images, though, it’s worth playing with as a way to express creativity, represent ideas, and enjoy interacting together. You might find out more about your child’s thought life than you ever would have guessed, and your child might discover a whole new world of expression and connection that they can make their own.